The cake knife caught the chandelier light like a warning flare—sharp, silver, unblinking. I hadn’t even inhaled the smell of chafing dishes and glazed ham when I registered the rest of the scene: a manila folder at my father’s elbow; champagne flutes lined like witnesses; a trash can pulled near the photo wall as if someone had planned for cleanup before the party began. By the time I reached the end of the long table, I knew this wasn’t a birthday dinner. It was a performance staged in an American living room, in a Phoenix suburb with stucco houses and citrus trees, with a flag on the porch and a driveway packed tight with SUVs that distended onto the curb like a parade had ended here by mistake.

Six p.m. sharp, dress nice, my mother had said. Bernardet always said those things like they were scripture. She loved the choreography of gatherings: the clink of glass, the moment everyone quieted at her signal, the way seating assignments could turn relatives into footnotes. She had called me three times that week to repeat the time and the clothing suggestion and I’d heard, in the brightness of her voice, the hum you hear in fluorescent lights before they flicker out. “It’s important,” she’d said, that particular sweetness stretching thin. “We haven’t had everyone together in a while.”

She was right about the turnout. The street looked like a late-October open house, cars teased onto lawns, neighbors stepping out to tug at leashes and inspect the spectacle. Inside, the thermostat had been set to impress. The living room air felt expensive. Emma, my sister, stood near the door in a dress that tried to look effortless and shoes that tried not to. Her smile didn’t fit her face, like someone had clipped it from a magazine and pasted it on.

“They want to make an announcement,” she said, voice pitched for a French-drain whisper even though no one was listening. She smoothed her skirt with the same motion she’d used since we were kids when she was pretending to be calm—palm flat, three swipes, exhale.

The dining room table had been extended with quiet urgency. Extra leaves slid into place created a runway of wood and expectation. I had sat there for school projects and flu fevers and Christmases and long, boring Sunday afternoons staring at a centerpiece like it might reveal a code. Now, chafers gleamed and steam rose in clean columns. Platters of rolls sweated under clean dish towels. The good silver made its annual appearance.

At the head of the table, my father stood and tapped his glass with the side of a butter knife. It made the sound you hear in movies right before something irreversible happens. The room hushed with the speed of habit. There were at least thirty people—relatives I’d hugged reluctantly at reunions, family friends who’d taught me to swim and corrected my posture, neighbors who’d loaned leaf blowers and asked for them back the next day. Faces flickered at the edges of my memory. Some were older. Some were the same.

Nicholas began a speech about responsibility, about decades of effort, about sacrifice. The words were right but his tone was wrong—the temperature of a board meeting, not a toast. He said “twenty-six” in a way that suggested it should be chiseled into granite. He said “opportunities” like the word belonged to him. He said “we” the way people do when they want a chorus. The cadence felt rehearsed. More concerning: his eyes didn’t look at me; they scanned the room like he was marking points on a map.

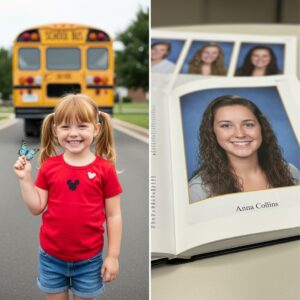

Before he could land the plane, my mother moved. She crossed to the wall where our family photos lived—a gallery of haircuts and major events: an eight-year-old with a missing tooth, an awkward middle schooler in an oversize polo, the two of us on Santa’s lap while Nicholas stood to the side wearing a watch he wanted people to notice. She lifted my high school graduation portrait, the one with the gown that made my shoulders look more decisive than they were, eased the wire from the hook with two fingers, and dropped it into the trash can someone had positioned below as if a decorator had planned for this exact outcome. The sound it made—a soft clatter, glass on plastic—is still in my bones.

She took another frame. Another. Each one lowered and discarded with the ritual efficiency of a decommissioning ceremony. Bernardet narrated her own actions in lines that sounded like she’d rehearsed them while arranging napkins. “You never appreciated,” she said, dropping a photo where I held a science fair ribbon. “You drained us,” she said, dropping a soccer team picture. “You embarrassed us,” she said, the two of us at a winter concert, a necktie crooked enough to irritate her from now until memory ended.

Aunties looked down. Cousins froze. My grandmother pressed one hand to her mouth like she was holding in a prayer. Someone in the cousin cluster lifted a phone, its camera eye peering over shoulders—a bright black pupil trained on the scene. The room didn’t breathe. Even the HVAC paused so it wouldn’t interrupt.

Nicholas slid a folder toward me across polished wood with the ceremony of a judge issuing something official. I opened it because the muscles in my hands still did what the world told them to do and found a document printed in a font that had probably been chosen with care. Invoice for parenting services rendered.

Columns and rows and the small smug thrill of a grid. Diapers. Formula. Pediatrician co-pays. Braces. School photos. Cleats. Field trip donation envelopes with lines for names. Car insurance with teenage premiums that made our house tense each June. College tuition numbers that read like oxygen debt. The bottom line was a number that doesn’t sound like a fortune until it’s used to measure love: $114,000. Nicholas had highlighted it in a pale flash of marker, lemon-yellow, the color of good intentions.

He told me I had two options: pay back every cent or never contact them again. He said “wasted” in a way that turned the money into a ghost. He said they were done being my parents. He said it in a voice that made nouns feel optional. I stared at him and thought, absurdly, about the time he taught me to tie a tie, the way he looped and tucked and then made me take apart the knot and do it again. I had never mastered it. I bought clip-ons after that and wore them like confessions.

Emma extended her palm toward me, fingers steady. “Keys,” she said, and for a second the word didn’t translate. It’s strange to have your vocabulary go missing in your own language. The sedan—mine in practice, not on paper—sat in the driveway with a new set of wiper blades and brakes that had started to complain. Nicholas explained the registration was in his name; he was transferring the title to Emma because she needed a dependable vehicle. Emma took my keys. They made a small sound when they dropped into her purse, a metallic manners lesson.

I scanned the room and saw a figure who did not belong. Ryan, my boss, sat at the far end, back straight, hands folded, the posture of a man waiting to say something managerial. He looked at me the way he looks at spreadsheets: with interest, without warmth. Bernardet gestured like she was revealing an honored guest at a luncheon. “We wanted him to hear the truth,” she said, and that was the moment my face went cool. If there had been cake, I would have cut it into precise, silent pieces and set each one on a plate with a fork.

Ryan stood and put on his HR voice, the one that’s supposed to sound neutral. He referenced a conversation he’d had with my parents earlier in the week. He referenced issues—character, work ethic—things people say when they’ve decided to convert feelings into policy. He said he was terminating my employment effective Monday. He said I could clear my desk. He did not make eye contact at the end. It’s difficult to shake a hand that isn’t extended.

I did nothing recognizably dramatic. I did not cry. I did not plead. I did not tilt my head and ask for an explanation that would be expertly phrased and empty. I stepped back from the table, walked to the front door, and left the house where I had learned the rules and all their loopholes. Outside, the desert evening had cooled, a small mercy. The porch light clicked on automatically. I called an Uber from the sidewalk and watched as the app’s little car icon crawled toward the drop pin like a beetle. Somewhere near the living room window, laughter rose and then stopped short, as if it had been pulled back by a string.

My apartment is a modest one-bedroom near an east-west bus line that gets me to work in thirty-five minutes if the timing hits, forty-eight if I miss the transfer. I closed the door behind me and said out loud to no one, “Okay.” It wasn’t the okay of agreement. It was the okay of engine check.

I’ve worked in tech support long enough to know that systems fail for predictable reasons. Overheating. Poor ventilation. Assumptions hardened into settings. I’d been cooling myself for three years, not to prevent failure but to delay ignition. Subtle comments had escalated to small exclusions, which had escalated to obvious disrespect. Tiny moves in a suburban chess match where image is king. My father wanted a doctor with his last name and a frame certificate that would bear witness in any room. My mother wanted a son who joined her social circles and performed their values with correct posture. I wanted out of the script. I chose a job that made sense to my brain and not to their bragging rights. I stopped attending their functions unless the function was love and not theater. I declined to date Emma’s friends whose last names came with membership dues. I started telling myself the truth even when the price was cold shoulders and pointed sighs and texts that dressed control as concern.

You don’t plan for humiliation. You prepare for patterns. I had a list. Not revenge. Not payback. Not even defense. Just names and dates and questions that had been whispered for years and then folded away because people don’t like to disturb the furniture in a room labeled “family.” There had been talk—at holidays, between refills of coffee—about estates and funds and distributions that didn’t find their intended targets. Polite eyebrows. Changing subjects. People with a talent for smoothing surfaces. I wrote the questions down exactly. I looked up county record portals and figured out how to request filings. I didn’t guess. I didn’t accuse. I asked.

Friday morning, my phone began to insist on itself. Missed calls stacked like receipts. Bernardet. Nicholas. Emma. The first voicemails were indignation wrapped in a scolding tone. How dare I walk out? I had embarrassed them. A good son would talk. By afternoon, the tone changed from lecture to earnest. We need to talk. There were misunderstandings. Could we get coffee? Saturday, the calls arrived like a pulse, high and rapid. On Sunday, Nicholas’s voice tried warmth and landed on weary. “We made mistakes. We should have handled things differently. Let’s figure out a way forward,” he said, as if the path was a hallway he could open with a key.

Between those calls, I made one that mattered. Marcus is my regional manager. He’s from Chicago, knows policies like gospel, and once told me in an elevator that the best people in tech support are the ones who are fluent in both the computer and the person using it. When I told him what Ryan had done—firing me without warning based on a private conversation with my parents—he didn’t respond for a full five seconds. Then he inhaled. “Sit tight,” he said. Two hours later: “Ryan is suspended pending investigation. You’re reinstated with back pay.” He said the words “violated procedure” like they were sharp tools he knew how to use. He apologized. He didn’t have to. I believed him anyway.

The car situation stung but didn’t open an artery. The title was in Nicholas’s name; I’d known that quiet fact like you know the soft spot of an apple. Emma could keep the 2015 sedan that needed rotors and a prayer. I would take the bus and scroll listings and save. Independence moves slower when you have to budget for it. It also arrives without anyone’s name attached.

Tristan called. My uncle has hands like he could fix anything and eyes like he decided long ago what not to see. He said he’d pulled the original will from a file at Grandma Eleanor’s house—dust still on the folder, lavender in the paper. He was supposed to receive fifteen thousand dollars. Nicholas had been executor of the estate. At the time, Tristan was told there was nothing left after expenses. Now, with the county filings in hand, he saw that the estate had cleared forty-seven thousand dollars after debts. Nicholas had claimed it all as costs. “I asked him about it back then,” Tristan said, his voice steady in that way older brothers’ voices get when they are the ones who lost. “He said there wasn’t enough. I let it go.” He paused. “I don’t think I’m going to let it go.”

Carol called, too. My mother’s sister has a laugh that used to fill rooms and a way of looking at you that can feel like a wind chime in a storm. She said she’d hired someone to look into the sale of their mother’s house. Two hundred ninety thousand at closing. A mortgage. Fees. After that: around one hundred eighty thousand. “She told me thirty was my half,” Carol said, voice thin with disbelief. “I didn’t ask for documents. I didn’t ask because that’s not what we did.” The investigator found bank transfers. The numbers did not agree with the story.

My cousin Ryan—the one who used to share cereal with me on mornings when the house was too quiet—reached out about the college fund Grandma had established. Fifty thousand put aside in 2005, to be divided among five grandchildren at eighteen. Nicholas named trustee. The bank mailed Ryan the history with the same courtesy it mails holiday calendars. The fund had grown modestly, safely. At each of five birthdays, the account emptied into an account with Nicholas and Bernardet’s names. “He told me the market lost it,” my cousin said, almost apologizing to me for believing a sentence that had come with a father’s voice.

Emma showed up with a lawyer whose suit looked expensive and whose name slid off my memory like oil. “He’s here to help,” she said, and the man smiled like a brochure. He talked about reconciliation, about how families who litigate rarely survive, about facilitated dialogue and better outcomes. I asked who had called him. “Emma,” he said, and then, under one raised eyebrow, “with background from your mother.” He said the phrase “everyone has their part” like a spell that might turn facts into mutual misunderstanding. I asked them both to leave. The lawyer left his card on my kitchen counter, where I used it that night as a coaster.

My grandmother texted. She is eighty-one and still writes in cursive like it’s a spiritual practice; texting requires both thumbs and faith. “Saturday. My house. Family meeting. You must come,” she wrote. It read like a summons. I pictured her at her small kitchen table with the fruit bowl that has always held more envelopes than oranges. I pictured Nicholas and Bernardet rehearsing arguments that sounded like explanations. I pictured Emma aligning silverware. I stared at the message, felt my pulse in my thumbs, and wrote back: “I won’t be there.”

At three forty-seven p.m. on Saturday, my cousin messaged: the meeting had combusted. Tristan had a lawyer and a copy of the will. Carol had printouts. My parents had phrases—“managing resources,” “unexpected costs”—and no receipts. Grandma had tried to keep order with a voice like a metronome. People who had spent twenty years being polite stood up one by one and stopped. The word “lawsuit” appeared in a living room where once there had been birthday candles and Boggle. People walked out in different directions. The front yard was a parking diagram. The light on the porch clicked on at dusk as if it hadn’t noticed anything unusual.

Sunday, my grandmother left a voicemail where disappointment came in notes. “Families face problems together,” she said. “You started this; you have a responsibility to help fix it.” She has always believed that smooth surfaces make for safer life. My mother inherited that belief and turned it into art. My father decided the surface itself was the achievement.

I was done polishing.

The calls kept coming until they learned to respect their own defeat. Between them, there were other visitors. Emma again, eyes rimmed red, apology and accusation stitched together into one frantic garment. “You have to help,” she said. “They’re falling apart.” I asked her if she’d known what the birthday dinner would be. She said no and then left a pause long enough to hold a piano. I showed her screenshots of texts I’d saved for three years like other people save recipes: messages where Bernardet called me an embarrassment; where she wrote, “We’ll teach him a lesson”; where Emma wrote back, “Maybe he needs a wake-up call.” Emma looked at me like the floor had disappeared and no one had told her. “I didn’t know the specifics,” she said, a phrase people use when they want to keep their moral math easy. I asked her why she took my car keys. “Dad told me to,” she said, a child’s answer in an adult mouth.

Nicholas waited for me outside my apartment building the following Tuesday. He stood with his shoulders like hangers, his face thinned into angles I recognized from photographs of his father. “We need to talk without spectators,” he said. He spoke about “managing family resources,” a phrase that tried to alchemize theft into stewardship. He said the money had gone to “important expenses” for the family, like the mortgage, like medical bills. He said he had intended to make everyone whole when “things stabilized.” He said Tristan wouldn’t have understood if he’d asked. He said Carol couldn’t handle a lump sum. He said the grandchildren would thank him one day for saving the family home. He said “home” like it was a person.

I asked him what part of responsibility included lying on a probate filing. He blew air through his nose like I’d asked him to admit to being hungry at dinner. He got angry with precision. “You have no idea what it’s like to be responsible,” he said, counting sacrifices like rosary beads: tuition, sports, braces, camp, the good school district, the extra math classes, the parking pass that cost a small fortune, the “we” that had made all of it possible. “We gave you everything,” he said, and in his voice I heard the line that had lived under my skin since before I could read. We gave, so you owe.

“I don’t owe,” I said, and it was not a rebuttal. It was a sentence marching on hard ground. “You invited my boss to a birthday dinner to fire me. You printed an invoice for love. You brought relatives to watch you throw my photos away. That wasn’t teaching me. That was punishing me because I stopped playing my role.”

“You can stop this,” he said, and for a second I saw the boy he must have been, trying to barter with a father who controlled the radio and the schedule and the temperature. “If you tell them you overreacted, they’ll back down. If you say you misunderstood, they’ll forgive.” He didn’t ask if it was true. He just asked me to lie.

“I asked questions,” I said. “Questions that led to records. Records that say exactly what they say.”

“You want to see us suffer,” he said finally, settling on a truth he could carry without breaking. “You’re cruel.”

“I’m tired,” I said. “And I’m done pretending that keeping the peace is a virtue when the peace is a lie.”

He said I was dead to him. I said that had already happened when the first frame hit plastic. He walked away in a straight line. I watched until he turned the corner and disappeared like a set piece rolled off stage.

Bernardet called from another unknown number the next day, her voice the soft skin of a fruit that’s still good if you eat it now. “We’re selling the house,” she said. The words moved slowly, like they’d resisted coming out. “We’ll settle with Tristan and Carol. We’ll move into an apartment.” She listed losses like she was reading off a weather report. “Emma is devastated,” she said, as if invoking her grief could rearrange mine. “You must be proud,” she added, a last attempt to anchor this in malice.

“I’m not proud,” I said. “I’m relieved.” She didn’t answer. In the silence, I asked a question for myself. “Do you regret it?” I asked. “The dinner. The photos. The way you did it.”

“I regret trusting people with information they weren’t sophisticated enough to understand,” she said, and for a moment I was ashamed of how familiar that sounded, how clearly it was her, how true to herself she remained even now.

The settlements arrived like mail that had always been coming. Tristan: thirty thousand—fifteen plus interest plus an apology no check line allows—enough to do something he’d been telling himself he’d do when things settled. Carol: one hundred fifty thousand, the difference between what she was told and what the math had always been. The grandchildren: forty-five thousand divided five ways, not enough to undo birthdays that came and went with hugs and a speech about how things were tight, but enough to pay for the semester fees that have a way of turning into something heavier than paper.

The “FOR SALE” sign sprouted in the front yard like a species of plant that thrives on bad timing. The listing photos cast the kitchen in the best light; the photographer knew which angle made the island look generous. I clicked through images and tried to feel something I thought I might feel—sadness, nostalgia, a tug in my ribs—but what I felt was the tinny aftertaste of an event that hadn’t been mine for longer than I had realized. Houses keep secrets. They also release them when the deed changes.

Emma posted broad, ad-friendly statements about forgiveness and family on her social accounts. Strangers told her to stay strong with exclamation points. People who didn’t know said the things people say about moving on. She didn’t name me. She didn’t need to. The algorithm did its work and pumped quiet sympathy into a timeline that thrives on incomplete stories.

My grandmother stopped calling, which is to say she decided to be silent in my direction—a language I know too well. Tristan texted: Thank you for asking. Carol messaged: I suspected. I never had the energy. My cousin sent a picture of five hands holding five checks, and I cried then, quietly, not for the money but for what it meant to see something intended become itself at last. Marcus swung by my cubicle and asked the kind of direct question that has saved me more than once: “Are you okay?” He told me Ryan was out, a formal finding with words that mean “we noticed and we acted” in legal. He said he’d like me to help write a training module about ethics in personnel decisions. I said yes because I wanted a version of this story to become useful to someone else.

On the twenty-ninth day, I bought a small cake at the grocery store—the kind with frosting roses that could survive a summer car ride. I lit one candle because I could. I ate a slice at my kitchen counter and washed the plate and put the rest in my fridge behind the milk like it was a secret I could retrieve when I felt like it. Twenty-six. No one would sing to me. It was the best sound I had heard all month.

I kept the manila folder in my desk because objects can hold the weight of their own absurdity and relieve your body of carrying it. The invoice makes me laugh in that way you laugh when you’re done being polite about someone else’s bad behavior. It’s a perfect artifact of a worldview—love as ledger, care as itemization, debt as a leash. It reminds me that some people will always tally where others hold. It reminds me to count other things.

The bus line outside my window has its own rhythm. The number 41 knuckles past every twenty minutes, reliable as heartbeats when you’re not thinking about them. You learn the stops, the timing, the faces. There’s a boy who boards with a skateboard and a backpack heavy with hope. There’s a woman who wears nurse scrubs and eats an apple like she has three minutes for the day. There’s a man who carries a small radio and listens to baseball like it is a church service. The driver nods to me now. I nod back and think about how systems can be kind when the people who set them up decide they should be.

I live near a grocery store where the produce manager rotates the cilantro like it’s a mission. On Saturdays, I watch families shop with calculators. On Sundays, I see couples with lists that split into tasks. I have my own rituals: coffee poured in a mug that makes no promises; laundry on a cycle that assures you it will end; a plant on the windowsill that pretends it’s bigger than it is. I am, I realize, one of those people who return library books on time because I know what it feels like to have someone else’s delay become your problem.

You might want to know if I miss them. That’s the question that lives under everything people think they want when they ask for updates. The answer is not simple and also it is. I miss a version of all of us that existed when the stakes were small—when Saturday mornings meant pancakes and a cartoon and a dog that didn’t listen. I miss the idea that parents are a place, that you can go there and be unexamined. But missing is not the same as wanting back. You can miss a house you’ve outgrown without wanting to shrink to fit its rooms.

I see my parents in ordinary places now—in a man whose shirt is pressed but not clean, who realizes at the register he has left his wallet elsewhere; in a woman who checks her reflection in every reflective surface as if she might catch herself looking wrong. I see them when I pass the kind of neighborhood where driveways are wet from washing on Saturday mornings, where people arrange decorative flags for seasons, where parties feel like exhibits in a museum of normal. I see them when I read stories that begin with small dishonesties and end with someone saying, “We did what we had to,” as if necessity is a detergent that can remove any stain.

One evening, a few weeks after the house sold (the listing agent took a photo with my parents in front of a sold sign, both of them smiling like the picture had a caption I couldn’t hear), I went to the old street and sat in my car a few houses down. The new owners had hung a wind chime and planted herbs in a bed that had been decorative rocks for twenty years. The porch light came on at dusk, same as always. A child’s bicycle lay on the lawn, its front wheel still spinning from a recent drop. Two adults and a kid carried in takeout in white paper bags that left grease halos, the universal sign of a meal they didn’t have to pretend was healthy. The new father put a hand on the doorframe before stepping through the threshold, a small gesture of ownership and maybe gratitude. I watched, allowed myself exactly thirty seconds of something like sadness, and then drove away because the light had changed and so had I.

Emma moved into an apartment across town with a friend she met at that boutique job. She likes her building’s pool. She posts pictures of sunsets and dogs that aren’t hers. She hasn’t contacted me since the day she saw her own words in my screenshots. She once liked one of my posts—a photo of a thrift-store desk I’d refinished. The algorithm served me her reaction. It felt like a dog-eared page.

Tristan and I went for coffee at a place where the baristas greet regulars by name because names are currency there. He told me he’s going to take his wife to the coast for the first time in years. He said he’d always told himself they would go when things were less tense. He wanted to show her water that went on forever. He asked me if I thought he should invite Nicholas. I told him to do what would make him feel okay if the story ended right after the trip. He nodded like someone had told him where the breaker box was.

Carol sent me a photo of a new couch delivered to a small place she rented after she left a situation that had required more tolerance from her than anyone should ever be required to carry. “It’s the first new piece of furniture I’ve bought for myself,” she wrote. “Ever.” She added a smiley face not because she’s someone who uses those easily but because the text needed help holding the emotion.

The grandchildren texted a picture of a group at a campus bookstore, holding overly bright sweatshirts and grinning like they had bought a future for a discount. “For once,” one wrote, “the timing worked.”

Marcus asked me to sit on a training panel about ethics and integrity in management. I told the story in a meeting room with a projector and a pitcher of water and a man from HR who said “values” in a way I decided to trust. I didn’t say my parents’ names. I didn’t need to. The lesson was the same without them.

A year will pass. It always does. Birthdays accumulate whether someone throws a party or not. Holidays come around with their timers and their tyranny. Family photos update on other people’s mantels. New babies arrive in posts on days when you aren’t expecting to feel anything and then do. Weddings happen in gardens where someone else’s mother cries into a handkerchief that matches exactly nothing and it doesn’t matter because real crying does not have a color story. In a hospital waiting room, a stranger will offer you half a sandwich and you will say yes because the generosity of strangers might be the most honest version of love’s economy we ever see in this country.

When people ask what happened, I tell them a version that fits in a conversation you can complete before the light turns red: my parents tried to invoice me for childhood; they invited my boss to a dinner; they staged humiliation because I didn’t become their scrapbook page. I asked questions that unlocked records. They lost a house they’d made into a monument to themselves. People nod and make sounds and say “That’s wild,” and then they tell me about their own versions in small pieces, like they are passing contraband across a border: a sister who became an accountant of affection; an uncle who turned executor into ATM; a mother who used secrets as currency; a father who called control “care.” We are a nation of stories told under our breath in grocery aisles.

I don’t pretend to be innocent in all this. I saved texts like I was building a case. I used my ability to plan and ask and endure. I provoked consequences and watched them land without interference. Does it make me vindictive? Maybe. Does it make me cruel? If refusing to lie along with the group is cruelty, then yes. Mostly, it makes me someone who decided that the cost of family peace was my own sense of truth, and I decided I was done paying.

If we were in a different kind of story, there would be a scene where my parents show up with tears honest as rain and words shaped like repair. There would be a holiday where someone passes the gravy and the silence tastes different. There would be a grandchild and a realization and a slow montage of summer afternoons at a park where the sun decides to bless everyone equally. Maybe that is a scene that will exist in a world I cannot see from here. Maybe not.

What I have is a bus pass and a job with a manager who meant it when he said “we’ve got your back” and a plant on a windowsill that survives because I remember to turn it twice a week so it doesn’t lean too far in one direction. I have a drawer with an invoice that tried to turn love into debt and failed. I have a phone that is quiet now. Do you know how loud quiet can be when you’ve built your life around not hearing your own needs? The quiet is a choir.

One afternoon in late spring, I walked past a park where the city had installed new benches that didn’t look like they’d last. A boy, maybe six, was trying to climb a low branch while his father—young in the way that feels fragile—stood below saying, “You’ve got it. I’m here.” The boy reached, grabbed air, missed, tried again, set his foot a little higher, made it. He turned and looked down at his father with a face I recognized from my own childhood in a house where branches were measured in grade-point averages and acceptable friend lists and a future planned like a grocery budget. The father said nothing at that moment. He didn’t say “good job.” He didn’t say “be careful.” He just smiled in a way that made the bench look like it might survive. He had probably been told by someone that you don’t praise outcomes, you praise effort, but what he did was praise presence by being present. It felt like an instruction from a kinder world.

On my birthday this year, I will invite exactly six people to my apartment: two coworkers who became something else called friends, one neighbor who brings me extra tamales in December, Tristan and his wife, Carol. I will buy a cake and not care that the frosting is too sweet. We’ll sit on my thrifted chairs and talk about shows and weather and what the city is doing to the buses this summer and someone will mention a big new project that is happening on the south side and I will say, “I read about that,” and we will argue in a friendly way about whether it is good. Around eight, I will cut more cake and say we have too much and send pieces home on paper plates with foil. I will wash the few dishes and think: this is all I ever wanted—conversation without performance, care without a ledger, love that doesn’t come with a threat of cancellation.

The cake knife will catch the kitchen light and, for a moment, I will remember that first glint under a chandelier in a house I no longer enter. The memory will not hurt. It will instruct. It will say: when someone tries to make your life into a production, you can walk off stage. The doors aren’t locked. The world is larger than the room where they are performing. There is a sidewalk and an app and a driver who will take you anywhere your seatbelt and courage allow.

If you read this far, you are looking for a map. Here is mine: If someone hands you an invoice for your existence, hand it back and go where you are not a line item. If someone says “we” and means “you,” learn a new pronoun that includes yourself. If “family” has become a code word for “control,” translate it into “history” and set it on a shelf where you can admire how it shaped you without letting it place you. Ask questions. County records are public. So is your right to tell your story without naming names. Use the tools available: policy, procedure, timing, patience. The system can work if you insist it does.

One last scene: a bus at dusk, the Arizona sky turning the color of peeled oranges and then, as the sun goes, that intense deep blue that makes palm trees look like a clip-art skyline. I’m in the window seat, forehead cool against glass, phone in my pocket, cake in a box on my lap for a coworker’s birthday tomorrow. The bus slows for a stop. A woman gets on carrying a sleeping toddler whose mouth is open in that way that tells you he has run himself out of daylight. The driver lowers the bus, sets the ramp, raises it again—small acts of dignity performed a hundred times a day that make a city livable. Behind me, someone laughs into a voicemail. The laugh is free of obligation. I look out at a house with a “For Rent” sign, a dog that understands something about leash etiquette his owner does not, a sky that doesn’t care if I am worth it because that is not how sky works, and I think: I am not a disappointment. I am not an invoice. I am not responsible for making anyone else’s story look good on paper. I am here, breathing, making a life that owes no one a receipt.

I get off at my stop and the bus sighs and pulls away. The evening smells like heat settling and someone grilling and citrus that forgot it was out of season. I walk up the stairs to my building, pass the plant I put on the landing because it likes the air there, unlock my door. Quiet greets me. The desk waits. The plant turns its leaves toward whatever the light is doing. The knife in my drawer waits for the next cake. The phone is still. In the space where a family used to be, there is room for an entire life. I begin.